International Women’s Day: WW1 WLA Inspector Sylvia Calmady-Hamlyn

Discussions at the February meeting of the Devon First World War Food and Farming Group began with a look at the part women played in farming during the war. One of the key figures in the promotion of women working on the land in Devon was Miss Sylvia Calmady-Hamlyn. Sylvia was part of a long-established Devon family that owned an estate on the edge of Dartmoor.

In January 1917 she was appointed as Inspector specifically to develop the new initiative to create a Women’s Land Army. She explained the scheme to the Women’s War Service Committee, later the Women’s War Agricultural Committee (WWAC).

‘[It] did not really touch on the kind of work the committee had been doing’, she said, by which she meant that this was an initiative to train women to undertake full-time agricultural employment, rather than one that sought to match local volunteers, many part-time, with local needs.

Seale-Hayne College today. Source: Graham Peers, Flickr.

Seale-Hayne College

Calmady-Hamlyn was appointed a governor of Seale-Hayne College, Devon’s planned new agricultural college, where the new Treasury-funded formal training course for women was established. Seale-Hayne was already providing some training, as the WWAC chair reported in March 1917 that there were 27 girls being trained and a waiting list of 18. The alternative route for training, via practice farms, was not taken up to any great extent in Devon (11 only by June 1917) but Calmady-Hamlyn worked to extend the opportunities for women, partly by developing specialisms such as forestry and hay baling, and then by the ‘big idea’ of the women-only farm. This was to be a way of convincing sceptics that women could manage a farm and undertake all the tasks associated with it.

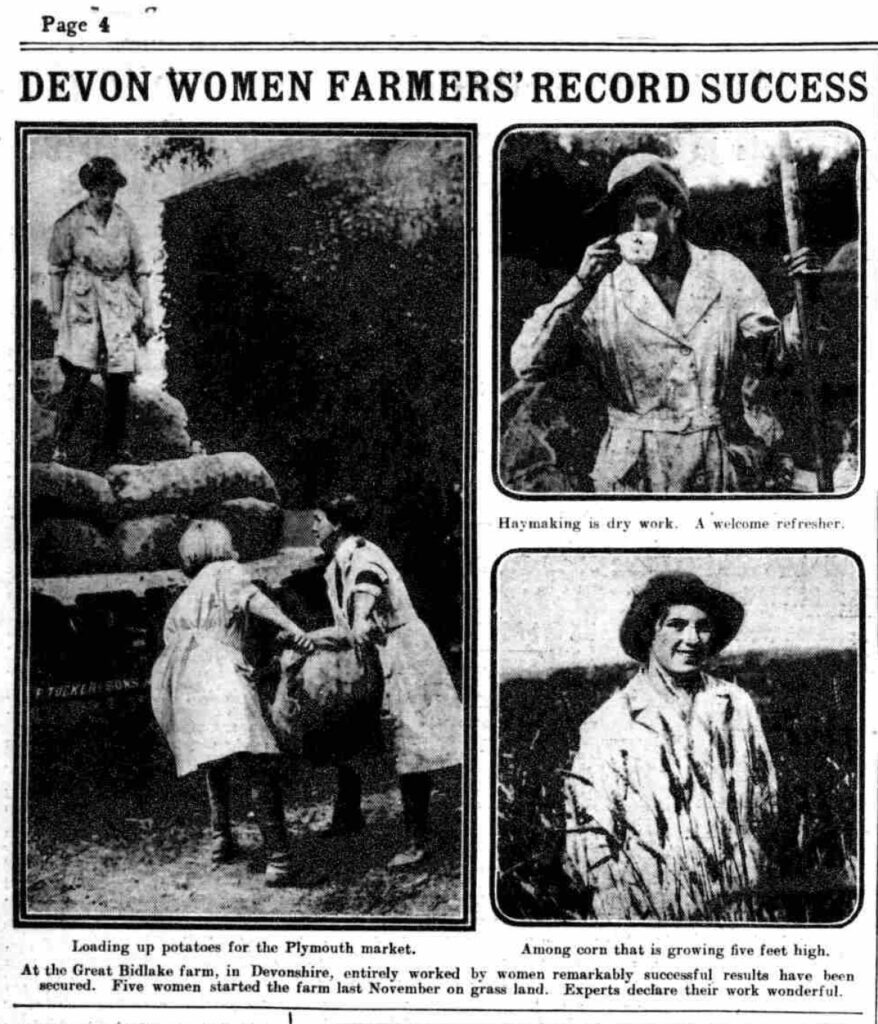

Great Bidlake Farm: the first all-female farm

The 130-acre farm was at Great Bidlake, close to Calmady-Hamlyn’s home in Bridestowe, and at her suggestion, with its owner’s consent, it was taken over by the Devon War Agricultural Committee in October 1917 and, with the advice and support of a local farmer, ploughing began and a small dairy was established. The farm was staffed by a forewoman and three girls.

In May 1918 Calmady-Hamlyn agreed to step into the role of County Organiser for the Devon WWAC. She organised recruiting rallies to keep up the supply of recruits, but acknowledged that the numbers achieved were not large: 178 girls placed and 29 in training in September 1918. By contrast, 4,300 women were in part-time work which meant that Devon had done ‘uncommonly well’. Great Bidlake Farm was no longer just a working farm, but had replaced Seale-Hayne as a training centre when the college buildings were requisitioned as a hospital. Although its first year’s balance sheet showed a deficit, this was due primarily to the inclusion of the setting-up costs as expenditure. Nonetheless the end of the war was the end of the Great Bidlake Farm experiment too. The County Council closed it along with other farms acquired under Defence of the Realm Act powers.

Post-War Memories

Twenty years after the end of the war, Sylvia Calmady-Hamlyn by that time best known in the county for her work for the Dartmoor Pony Society, related her memories of her time with the Board of Agriculture to a reporter from the Western Morning News. They wrote the account of her interview:

‘Miss Calmady-Hamlyn was the first and only travelling inspector appointed by the Board of Agriculture. [She covered the area between London and Land’s End] She travelled six days a week, by any available trains. Her Land Army overall, thick topcoat, heavy boots and one shilling hat, with its mystifying badge, caused a certain amount of consternation in first class coaches when important officials were scheduled to travel.

“Usually I left home with a good supply of hard-boiled eggs”, she confessed, “as food was hard to come by then and many a night I’ve arrived at my destination too late to obtain rations. Once, after being without food all day, I was offered a bottle of soda water, by way of refreshment. On Mondays the hard-boiled eggs were appreciated. By Wednesday their flavour began to pall. When Thursday arrived I felt I never wanted to see an egg again as long as I lived”, chuckled Miss Calmady-Hamlyn. “It was a treat then to buy a pasty filled with rice at Truro Station”.

‘Never in her life has this amusing woman possessed such a wonderful hat as that she bought for a shilling that served her throughout the war. So, at least, she loves to aver. Her most prized possessions now are the badge from that hat and the six stripes that remain as evidence of every six months she gave to organizing the Land Army. Her chief regret is that the hat itself is no more.’

The Western Morning News celebrated how Land Girls held Miss Calmady-Hamlyn in much awe. Mrs Bootes, as she was by 1938, remembered the arrival of the inspector at the Cornish training establishment during the war.

‘I had been at Tregavethan for precisely a week’, she said. ‘One day before going off to the fields we were warned of Miss Hamlyn’s impending visit. Returning I jumped from the cart in which I was riding and ran to join the ranks. “Oh, no”, said Miss Hamlyn, “Go back and put your horse away”.

I had never attempted such a thing before. Patiently Miss Hamlyn watched me undo every buckle in the breeching and lead the horse into the stable. I don’t think those buckles had ever been undone before. My hands were scratched and bleeding with the effort. When it was done Miss Hamlyn remarked laughingly that she had never seen the job done so thoroughly’.

Calmady’s post-war work

Calmady-Hamlyn had always believed that their work was designed only to fill the gap until the men came home. She retired to her pony-breeding business, receiving the MBE for her work. Having demonstrated her effectiveness in public service, however, she found herself almost immediately recruited to two new spheres of work in the county: the development of Women’s Institutes, and service as one of the first women magistrates.

Undoubtedly there was hostility expressed by some farmers to the work of Calmady-Hamlyn and the Devon WWAC, particularly when they were criticised for their poor rates of pay. But there was support from others, for example from the Barnstaple branch of the National Farmers’ Union; from the individuals who lent their farms for demonstrations of women’s work; and from Mr Ash, the farming neighbour at Great Bidlake who offered the women advice and instruction. The full-time members of the Women’s Land Army may only have made a small contribution to the labour force in Devon, but the women recruited through the registrar scheme performed a valuable role in replacing the pool of men whom farmers had in peacetime been able to call on from their rural trades at times such as harvest.

Dr Julia Neville

Research Co-ordinator, Farming Fishing and Food Supply in Devon during the First World War

Dr Julia Neville is working on an AHRC-funded project on Food, Farming and Fishing in Devon in the First World War. This is led by the University of Exeter and Devon History Society in conjunction with the University of Hertfordshire, and funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council as part of research for the Everyday Lives in War Engagement Centre. For more information, please click here.